Borkowski Media Trends: Plumbing Crisis, The Portal, King Charles's Portrait

Plumbing new depths

The media and public alike are hungry for stories of altruism in the current climate. During Covid-19, we had Sir Captain Tom (RIP) and his daughter’s charity-funded swimming pool (RIP). Marcus Rashford’s campaign for free school meals made him a veritable (if temporary) saint. And the cost of living crisis brought us James Anderson, “Britain’s kindest plumber.”

With tales of saving the life of an octogenarian on the verge of suicide because she didn’t have any hot water or providing a replacement boiler free of charge for a woman living with cancer. The tales of his selfless acts for vulnerable people garnered regular plaudits in the local Lancashire press and broadcast spots on This Morning and The One Show. Actor Hugh Grant even donated £20k to help the plumber continue his good work. But now a BBC investigation has made Anderson’s claims and his company Depher crumble.

From accusations of reusing images of the same pensioners several times to tell different stories of good deeds to proof Anderson had published photos of at-risk people without consent, the BBC also allege that he spent company funds on a house and car. Depher’s social media accounts have now been deleted, but it is shocking that suspicions weren’t raised earlier, considering the massive spotlight Anderson turned on himself and how much conflicting evidence was already available in the public domain.

It seems to be Anderson’s peers who outed him first, with a March interview on Fix Radio’s the Heating & Plumbing Show featuring defensive and rambling responses to simple, incisive questions on Depher’s practices. It might not be human nature to doubt charitable endeavours, but this story is just another reminder that journalistic cynicism still has an essential role in the British tradition of feel-good stories.

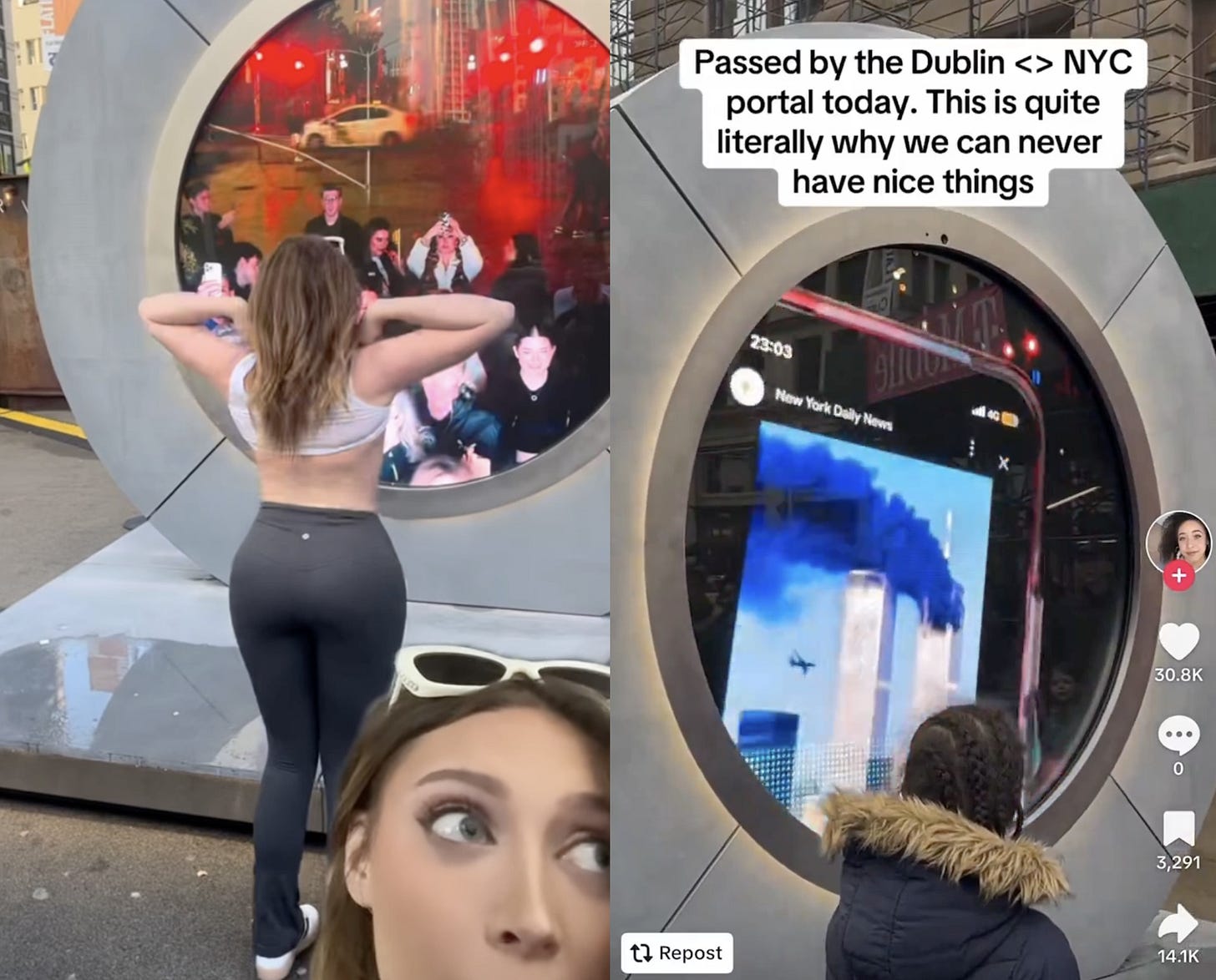

Viral incidents shut NYC-Dublin Portal

A 'Portal' linking the people of Dublin and New York City via a continuous livestream has been shut following several inappropriate viral moments, including an adult entertainer flashing at the Dublin crowd in an "act of revenge" for the Dublin side sharing a picture of the September 11 attacks from a phone screen. This public art installation was an attempt to unite the people of New York City and Dublin in 24/7 real-time. But this wholesome stunt placed too much emphasis on New York and Ireland's "deep historical and cultural bond" (to quote the press release) and not enough thought or consideration that this "technology sculpture" was a powerful meme generator.

Considering that The Portal was live for over 100 hours, for most of its lifespan it connected thousands of people across two continents. It provided the site for reunions with old friends and even a proposal, with many moments going viral on social media. However, while this was a real-world activation, there was enough anonymity for people to behave like they do on platforms like Twitter or Reddit and misbehave to force a reaction for attention. And for all the tender moments, you only need a few bad actors and their actions to go viral and you have a crisis.

As this was branded as an art installation, the organisers have a lot of leeway to claim this was a kind of social experiment or even a moment of learning. But in reality, this was a stunt that was always going to end in tears because the public in crowd mode can't behave themselves. Once something becomes a meme, there's an incredibly high chance that there's a permanency to the negative viral moment that will stick around for the duration The Portal is up and may even define its legacy.

In our post-social media world, organisers must consider how my event can be intentionally derailed and turned into a meme. You can't stop freak happenings from becoming a one-off viral moment; The Portal was anything but this. It was a textbook Boaty McBoatface situation. Fortunately, the stakes here are low enough that this won't cause anyone any reputational damage.

Charles Portrait has British Public Seeing Red

Whilst King Charles himself maintains a relatively low profile as he continues to battle cancer, his first royal portrait since his ascent to the hot seat was the topic of national conversation in the UK for much of this week.

Jonathan Yeo’s large and boldly stylised portrait of the king emerging from an ethereal (some say infernal) red mist accompanied by a monarch butterfly has totally polarised the UK but interestingly along different lines than usual culture wars clashes stemming from Buckingham Palace.

The portrait received harsh criticism from commentators ranging from the Guardian art critic to Lorraine Kelly, but was also defended for its modernity and self-conscious weirdness by quite a few commentators who could hardly be described as royalists.

As with all articles of visual culture, the portrait instantly became a meme, ‘Vigo the Carpathian’ (a Ghost Busters II baddie) trending on the day it came out amid a slew of jokes around the work’s infernal oddness.

Amazingly, and in yet more ammunition for the meme community, it wasn’t the only painting-related controversy in the world this week, as Australia’s richest woman Gina Rinehart made headlines for demanding that the country’s National Gallery remove a less than flattering portrait of her from a satirical exhibition that also features a “wonky” King Charles.

When all is said and done the overall impact is fairly minimal; given that it was once the Western world’s foremost visual projection of power and legacy, portraits of the rich and powerful these days have very little impact on the subject’s long-term reputation, and Charles’ legacy will ultimately remain undiminished (and unburnished) by his hellfire, just as Gina’s will survive her caricaturisation.